Scroll to:

Vassiliy Barskiy discovering the Christian Architecture in Syria

https://doi.org/10.15829/2686-973X-2020-2-21

Abstract

Keywords

For citations:

Buzykina Yu.N. Vassiliy Barskiy discovering the Christian Architecture in Syria. Russian Journal of Church History. 2020;1(2):22-34. https://doi.org/10.15829/2686-973X-2020-2-21

One of the greatest travelers and researchers of the Middle East in modern history, Vassiliy Grigorovich-Barskiy has a specific range of interests and consequently routes, instead of his European fellows. He focused not on antique artifacts, but on the Orthodox shrines. The subject of our study will be the reasons for choosing objects to visit and the scientific results of these visits [Buzykina 2020]. Barskiy ignores some shrines extremely important for all the Christians (for example, Qalaat Semaan, place of feat of Simeon Stylites), at the same time he pierces into other ones, preparing very carefully, risking his life, health and property. Sometimes this behavior is understandable. It is annoying to return to Kiev having reached Egypt but to miss the monastery of St. Catherine on the mount Sinai and return to Kiev. Sometimes Barskiy’s choice looks rather strange, and cannot be accounted for his desire to visit an interesting place he accidentally found out about. Such a place will be discussed in my article. This is ancient Izra town (Syria, Hauran region), where the 6th century churches of St. George and the Church of the Prophet Elijah stand, miraculously preserved till nowadays.

Barskiy was perhaps the first European to compile their scientific descriptions and publish Greek inscriptions. At the same time, he did not attend or even mention complex of equally ancient churches located in Bosra. Using the example of visiting Izra and its churches, we will try to answer the question about the reasons for choosing objects to visit.

In 1734, when Barskiy was studying the Greek language with didascalos Jacob in Tripoli (Lebanon), began an epidemic. Before the roads closed, Jacob was called by the Patriarch of Antioch, Sylvester Cypriot (September 27, 1724-1766), to Damascus [Hage 2007]. Upon arrival, Jacob preaches to the locals, with whom, for their part, Catholic missionaries work very actively and successfully1. So Barskiy was at the court of Patriarch Sylvester, who loved him as a son and personally made him a monk, saving our hero’s name, in honor of St. Basil the Great. Barskiy, in his turn, composed praises to Basil the Great and to Patriarch Sylvester. He recited both at a meal in honor of his tonsuring.

Additionally, Barskiy presented to the patriarch a view of Antioch drawn by himself. Patriarchs of Antioch had to leave his see and to live in Damascus because there were no more Christians in their city. The patriarch was touched so deeply and first didn’t want to let him go. However, later Sylvester gave Vassiliy the necessary papers and blessed him to go and establish Hellenic-Greek school in Kiev [Stranstvovaniya 1886].

Barskiy left, but not to Kiev, moreover in exactly opposite direction — southwards from Damascus. He went to The Sea of Galilee, took a swim and a few stones from its shores had a look to the springs of Jordan River and the ancient city of Banias (Caesarea Philippi) [Stranstvovaniya 1886:221].

From there, his path turns to the east, to the area of Hauran, which he calls Haran, maybe having Biblical Harran on his mind. Hauran (Αυρανίτις, Jabal al-Druze, country of caves; Ezekiel 47:16-18) — mountainous area east of Jordan, south of Trahontida and Damascus, at Bashan (Psalm 67:16), on the border of desert, about 100 km east of the southern coast of Sea of Galilee [Rineker 1891:20-21].

The traveler explains his decision by pious and scientific curiosity, which is the same for him: “I also heard from local Christians that in two days walking from here there is the famous place of Haran (sic!), the metropolis that refers to the authority of the Patriarch of Antioch. Once it was an independent kingdom, but now it is desolate and depopulated; it contains buildings worthy of surprise and praise. Having heard this, I decided to go there” [Stranstvovaniya 1886:222].

Such scientific zeal brings to mind the British archaeologistsspies of the early 20th century who studied the Middle East, such as Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell, Thomas Edward Lawrence and their lesser-known German colleagues.

Having penetrated into Hauran with the help of a local guide, an Arab Christian, Barskiy describes the area, people living there, architecture, especially Christian churches, and publishes Greek inscriptions with observance of the lines and translation into Russian. Where the letters could not be read, he left an empty space [Stranstvovaniya 1886:231].

In other words, Barskiy renders the inscriptions in accordance with the European scientific tradition. This is how they are transmitted by Cornelius de Bruyn [de Bruyn 1698:335-358], whose writings he supposedly read2.

The city of Isra or Ezraa (in ancient times — Zorava or Zorabene) is located in the eastern part of the Daraa governorate, 30 km from the town of the same name, through which the Hejaz railway passed, on the Hauran plateau, at an altitude of 599 meters above sea level. This Canaanite city is mentioned in the Bible and appears on the tablets of the Amarna Archives (1334 BC). The city flourished in the Roman era, as evidenced by the surviving Latin inscriptions, completely ignored by Barskiy, although he spoke Latin and fixed in his diary Latin inscriptions on the Plague column in Košice and on the House of the Virgin in Loreto [Stranstvovaniya 1886:19, 62-64]. The local landscape — the plateau — turns the region into a natural fortress that is almost impossible to capture by force. Hauran was turned into Christianity very early due to its geographical proximity to the Holy Land.

In Byzantine times, in the 6th century, this city had the second most important episcopal see after Bosra in the province of Arabia. The churches of St. George (on the site of a pagan sanctuary) and the prophet Elijah were constructed during this period. The see was abolished after the Arab conquest, but the Christian population remained.

In 1516, Syria fell under the rule of the Ottomans, and agriculture degraded. According to Ottoman taxpayer lists, at the end of the century, Izra was mostly populated by Christians (175 Christian households and 59 Muslim households) [Hütteroth 1977; Piccirillo 2002; Porter 1855:221-232; Murray 1841; Sartre 1985; Sartre 1991; Sharon 2007]. Shortly before Barskiy’s visit, at the beginning of the 18th century, civil strife broke out among the Lebanese Druses, and the losing clans, Al-Atrashi and Hamdans, moved to Hauran, in an area called Jabal Druz (Druze Mountains)3 [Pozdnjakov 2018:492]. The event contributed to the growth of tension, and this area did not obey anyone at all until the beginning of the 20th century [Lawrence 2015:334].

As for religious subordination, the city was traditionally under the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Antioch under both the Arabs and the Ottomans, but in 1724 there was an ecclesiastical division into the Orthodox and Melkite Greek Catholic churches. Barskiy’s patron, Sylvester the Cypriot, was Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch, he waged an intense (and in many respects hopeless) struggle against Latin proselytism, which took away his flock in front of his eyes, and the situation in this region should have worried him.

At the time when Barskiy was there, in 1734, the Hauran region remained desolate and the Melkites (Latins), of course, should have been interested in it. Already in 1687, the Vatican annual Annuario Pontifico mentions the Catholic bishop of Bosra for the first time, although in 1724, at the time of the foundation of the Melkite church, there was no corresponding diocese.

It appeared later, in 1763, when the Melkite patriarch Michael Jawhar appointed the first bishop of Bosra Francesco Siage, who was one of the members of the Melkite Basilian monastic congregation. After chirotony, he took the name of Cyril and later became Patriarch. Nowadays, Izra is under Melkite jurisdiction, within the framework of the archdiocese of Bosra and Hauran, with its center in the city of Habab. Thus, in 1734, the Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch still had a chance to win back Hauran, and he had to try to take advantage of it, which, as we assume, is the reason for the keen interest of Barskiy (who already wanted to go home) to this region. This assumption is also supported by the fact that he did everything to be unrecognizable, and, having examined Hauran, immediately returned to Damascus to Sylvester.

Having reached the city, Barskiy describes its unusual architecture in four points: 1) the material for all buildings is black stone (basalt); 2) floors in buildings are made of stone planks; 3) entrance doors in churches and houses are made swinging, like the royal doors in churches, and these doors are also made of stone; 4) the buildings are folded dry from stones, very tightly fitted to each other, so that the end of the knife will not be pushed between them [Stranstvovaniya 1886:225].

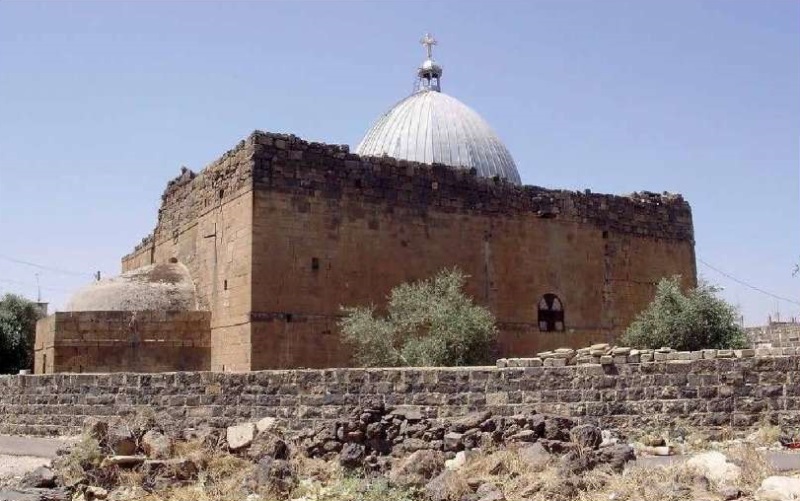

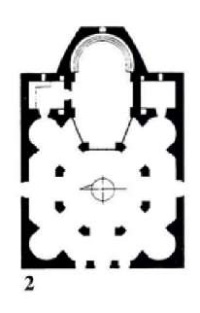

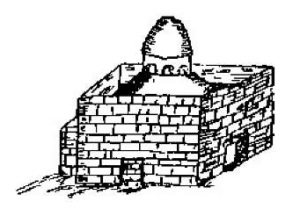

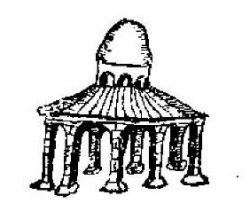

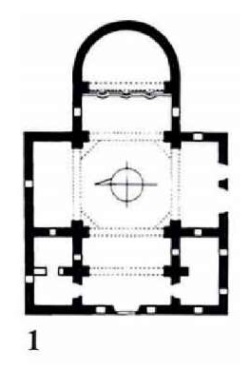

Then he proceeds to describe churches and other buildings, and the first is the church of St. George (Fig. 1, 2). According to the inscription above the entrance, it was built, in 515 on the site of a pagan temple of a local deity and is one of the oldest active Christian churches in the world. Its plan is an octagon inscribed into a square, formed by pillars on which the arches rest (Fig. 3, 4). “In the mentioned city there is a wonderful church of the Holy Great Martyr George. It has three gates, from the north, south and west. The side ones are closed with stones, the western ones are always open. They are made of two stone tablets, so they open with great difficulty. Nevertheless, they are always open, because the temple is empty and there is nothing inside except the divine altar and the holy trapeza (sic!), where Christians often worship when leaving; they bring and kindle censers and oil. This church is very famous there, because of the signs and actions performed by the power of the holy Great Martyr George. He heals the weak, but hurts ones who harms him. Therefore, none of the Muslims dares to harm the church. Many of them thought about how to turn the church into a mosque, destroy the altar with holy trapeza and create another in the south, as they are supposed to worship for the sake of their Mohammed, because, as they believe, on the south side came out of Jerusalem, which is from there in 14 days’ journey. They have thus ruined many fine Christian churches because of our sins; and this one still stands because of the power of the holy great martyr George. Outside it is square, made of beautifully carved stone, and inside it is round, based on eight pillars, looking like a beautiful lantern. From the neck to the pillars and from the pillars to the outer walls that form a square, it is covered with long stone boards, in an amazing way, as I have drawn here: on the right is its inner base, on the left is the outer (Fig. 4, 5). There is this Greek inscription above the western entrance, on a large and wide stone, I give you a Russian translation: God’s house was once the dwelling of demons / ΘEOY ΓΕΓΟΝΕΝ ΟΙΚΟΣ ΤΟ ΤΩΝ ΔΑΙΜΩΝΩΝ ΚΑΤΑΓΩΓΙΟΝ / Saving light shone where there was darkness / ΦΩΣ ΣΩΤΗΡΙΟΝ ΕΛΑΜΨΕΝ ΟΠΟΥ ΣΚΟΤΟΣ ΕΚΑΛΥΠΤΕΝ / Where there were sacrifices to idols — now there are angelic choirs / ΟΠΟΥ ΘΥΣΙΑΙ ΕΙΔΩΛΩΝ ΝΥΝ ΧΟΡΟΙ ΑΓΓΕΛΩΝ / Where God was angry — now He can be prayed / ΟΠΟΥ ΘΕΟΣ ΠΑΡΩΡΓΙΖΕΤΟ ΝΥΝ ΘΕΟΣ ΕΞΕΥΜΕΝΙΖΕΤΑΙ / A man, a Christ-lover, an authority, named John / ΑΝΗΡ ΤΙΣ ΦΙΛΟΧΡΙΣΤΟΣ Ο ΠΡΟΤΕΥΩΝ ΙΩΑΝΝΗΣ / Son of Diomedes / ΔΙΟΜΗΔΕΟΣ ΥΙΟΣ / From his gifts, he brought to God something vision worthy / ΕΞ ΙΔΙΟΝ ΔΟΡΩΝ ΘΕΩ ΠΡΟΣΗΝΕΓΚΕΝ ΑΞΙΟΘΕΑΤΟΝ / Building / ΚΤΗΣΜΑ / Confirmed in this a virtuous holy martyr / ΙΔΡΥΣΕΝ ΤΟΥΤΟ ΤΟΥ ΚΑΛΛΙΝΙΚΟΥ ΑΓΙΟΥ ΜΑΡΤΥΡΟΣ / George / ΓΕΩΡΓΙΟΥ / Honest relics, because he appeared to John himself / ΤΟ ΤΙΜΙΟΝ ΛΙΨΑΝΟΝ, ΤΟΥ ΦΑΝΕΝΤΟΣ ΑΥΤΩ ΤΩ ΙΩΑΝΝΗ / Not in a dream, but in reality, in the year Θ. Of the year YI / ΟΥ ΚΑΘΥΠΝΟΝ ΑΛΛΑ ΦΑΝΕΡΟΣ ΕΝ ΕΤΙ Θ ΕΤΟΥΣ ΥΙ [Stranstvovaniya 1886 1886:225-227].

Fig. 1. Church of St. George in Izra.

©photographer Vasily Nesterenko.

Fig. 2. Church of St. George in Izra. Interior.

©photographer Vasily Nesterenko.

Fig. 3. Church of St. George in Izra. Plan

(after: Dentzer 1993).

Fig. 4. Church of St. George in Izra.

Drawing by Grigorovich-Barskiy. Appearance

(after: Stranstvovaniya 1886).

Fig. 5. Church of St. George in Izra.

Drawing by Grigorovich-Barskiy. Eight

(after: Stranstvovaniya 1886).

Barskiy described some kind of structure not far from the church of St. George, but now, judging by the travelers’ blogs, this place is fenced off as an archaeological park and is a conglomeration of architectural fragments from different times. Barskiy also carefully examines them and sketches the classicist portico of the new church, on the facade of which it is written: “Lord, bless Athanasius Zinodor” [Stranstvovaniya 1886:230].

The Church of the Prophet Elijah is located next to the Church of St. George (Fig. 6, 7). It dates back to 542, has a plan of the type of an inscribed cross, is also active and now belongs to the Greek Catholics. In the same city, there is the devastated church of the holy prophet Elijah. This is known from the inscription above the entrance, although not everything is clearly read there, the name of Elijah the prophet is identified; and the following is written: At his expense, the temple of the prophet Elijah / ΟΙΑΠΟΖΟΡ ΕΞ ΙΔΙΩΝ ΝΑΟΝ ΗΛΙΟΥ ΔΙΑΚΕΝΕΤΙΥ... / created at the time of God-loving Bishop Varus / ΕΚΤΙΣΑΝ ΕΠΙ ΟΥΑΡΟΥ ΘΕΟΦΣ ΕΠΙΣΚΟΠΟΥ (sign of the cross in a circle) ΩΕΠΙΓΑΡ / Bishop (sign of the cross in a circle) death (sic! — Yu.B.) Ο ΘΣ ΠΟΤΜΟΝ ΒΟΗΒΩΣΜΑΙΣ [Stranstvovaniya 1886: 230-231].

Fig. 6. Church of the prophet Elijah in Izra.

From open sources.

Fig. 7. Church of the Prophet Elijah in Izra. Plan

(after: Dentzer 1993).

We suppose that Barskiy was the first European who had described these churches. In the European writings he could read there are no descriptions of Hauran. Neither Elzearius Horn described them4 [Buzykina 2020 (in print)], nor Cornelius de Bruyn. The great traveler Johann Ludwig Burckhardt (1784-1817), who is supposed to be the first European who describer monuments of Izra, came here only in autumn-winter of 1810 [Burckhardt 1822]. He composed description of Hauran [Burckhardt 1822:51-119], and Izra as well, which he visited on November, 10-12, 1810. Burckhardt went to Hauran with knowledge, that there are many antiquities there, Greek Inscriptions and Christian population. He also knew Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch, whose residence was still in Damascus, and he also travelled incognito wearing local garments and having local guides. In the town of Izra [Burckhardt 1822:52-63] he stayed in a house of Greek priest, who was his guide for temples and ruins of Izra. Among places of interest, he describes the churches of St. Eliah and St. George, including specific features of architecture, safe state and reproduces the inscriptions [Burckhardt 1822:60-61]. Subsequently, the region has become a real place of interest for British and German researchers. Soon the monuments of Izra, along with churches of Bosra, took their place in the history of Christian Architecture [Porter 1855:224, 227 (St. George); 227 (St. Eliah)].

Church of St. George was studied by leading European and Russian scientists, among them N.P. Kondakov, who proposed an original interpretation of the shape of its dome [De Vogüé 1868:Pl. 21; Waddington 1870. no. 2481, 2482, 2483, 2488, 2496, 2498; Architecture 1903:411-413; 1929:121-125, ill. 122-123; Kondakov 1904:75-78; Lassus 1932:13-45; Messerer 1952:7-31; Karnapp 1966:178-186; Restle 1971; Odenthal 1983:123 f; Restle 1984:261-66; Lassus 1985:229f; Restle 1989:373-84, espec. 377-381, fig. 103; Dentzer 1993:82-101; Scheck 1999:401; Fartacek 2003:60-64]5.

The nine-meter dome collapsed during an earthquake in 1899, but an American archaeological expedition managed to photograph the church almost the day before. They supposed that the dome was made of concrete [Architecture 1093:413]. Kondakov also saw the building still intact, in August-December, 1891. He assumed that this dome was not original, and even indicated the level to which the structure was authentic [Kondakov 1904:75-78]. Indeed, the dome of the church of St. George collapsed at least one time before Kondakov saw it, as a result bombing it by the Egyptian governor Ibrahim Pasha in 1838. The current dome was erected at the expense of the Russian Emperor Nicholas II. Barskiy’s drawing shows an ancient, still whole dome, made of stones. Although St. George’s Church is Orthodox, Muslims also revere this place, which Barskiy also noted. The Church of the Prophet Elijah is similar to the Church of St. George, but its dome is new, previously there was a wooden construction on its place. Burckhardt describes the building in more detail than Barskiy, and gives many inscriptions, while Barskiy published only the first one, above the entrance to the vestibule [Burckhardt 1822:59-60]. The Church has also been studied by leading scholars [Dentzer 1993:91; Scheck 1999:402; Waddington 1870: no. 2481, 2485, 2490, 2497; Lassus 1932; Messerer 1952:52-54; Restle 1989:373-84, espec. 376; Kondakov 1904:78].

After leaving Izra, Barskiy inspects another curious building, located three hours away, where a certain Regional Church Council took place. He describes the building, fixes the inscriptions. After that, Barskiy urgently returns to Damascus, without even going to get his clothes to a priest from a Christian settlement across Lake Gennesaret, apologizing that from the place where he ended up, he had to go two days in very dangerous places, and to Damascus only day. Fortunately for Barskiy, he met a caravan of pilgrims returning from Mecca and joined in, posing as insane. He enters the city with Hajji, incognito, manages to visit a charming hajji hospice and the forbidden for Christians Umayyad mosque, built on the site of a Christian basilica, where the head of John the Baptist is kept. All this resembles an adventure novel, but some conclusions can be drawn from what Barskiy said.

So, Barskiy completed the first Russian-language scientific description of the ancient (6th century) churches in Izra (Ezra) — St. George and the prophet Elijah, as well as other, later buildings. We are inclined to assume that this could be the first description of them by a European. It should be emphasized that this is a scientific description, with the fixation and translation of the inscriptions, valuable as itself and also because of the fact that Barskiy sketched the unpreserved dome of the church of St. George.

The quality of the drawings and the lack of identified prototypes testifies to the fact that he drew from life, and did not redraw from someone from his predecessors, although earlier he could make his drawings on the basis of others, in particular, Elzearius Horn and Cornelius de Bruyn.

Barskiy borrowed the principles of describing cities and the method of sketching, piece by piece, to reveal the structure, from his European colleagues. All the buildings described are related to Greek-speaking Christianity in this area. The very fact of their existence could serve as an argument in favor of the legitimacy of the claims of the Patriarch of Antioch to these lands.

In addition to architecture and epigraphy, Barskiy indicates the religious affiliation of the population, among which there were Christians. This information, which looks (and is) quite scientific, should have had practical application. It can be assumed that the initiative to visit Hauran did not belong at all to Barskiy, but to Patriarch Sylvester of Antioch; Barskiy simply does not write about this in the text of his notes. Since Sylvester shortly before this tonsured Barskiy a monk, he could become his spiritual father and govern the life of the newly-minted monk Basil6.

From this point of view, it does not seem unusual that, having found himself in Cyprus, where Sylvester was from, Barskiy immediately got to Archbishop Philotheus, with whom Sylvester was familiar, and received a reception, housing, a table, and a place as a teacher of the Latin language. When the earthquake and epidemic struck, Barskiy undertook a real expedition, describing the Christian churches of Cyprus. The result was a description of the island, which is still an important source for historians and art historians. Barskiy kept contact with Sylvester till the end of his life.

Barskiy’s scientific descriptions turn from a game — into a purposeful activity that someone directs, and therefore from the moment of the Syrian adventures they become like real expedition materials. Presumably, one of these scientific leaders was Patriarch of Antioch Sylvester the Cypriot.

Aknowledgements. I express my gratitude to the photographer Vasily Nesterenko, whose photographs of the church of St. George were used as illustrations, and to Dr. Eva Haustein-Bartsch for helping with Western literature.

Relationships and activities: not.

1. In 1724, a split occurred between supporters and opponents of the union with the Catholics. Both were in Damascus. Sylvester was the leader of the opponents of the union, and Cyril Thanas (September 20, 1724 — July 30, 1759) was a Latin protege and the first Melkite patriarch of Antioch and the whole East.

2. Buzykina Y.N. Presentation of the East and Drawings by V.G. Grigorovich-Barsky. Report at the conference “Fabrica Mundi: Illustrating Scientific Ideas in Antiquity, the Middle Ages and Modern Times”. February 19-20, 2020.

3. Nowadays — Jabal-al-Arab (Mountains of the Arabs).

4. Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. lat. 9233. pt.1, Vat. lat. 9233. pt.2, Vat. lat. 9233. pt. 3.

5. See also: Restle M. Die Erforschungsgeschichte der Architekturdenkmäler im Hauran. Wien. Electronic resource: www.web.archive.org/web/20160304112401/http://www.hauran-monuments.eu/images/hauranforschung.pdf (Date of appeal — 17.04.2020).

6. Barsky describes his tonsure as follows: “[Patriarch] himself, tonsured me — unworthy — into a subdeacon and a monk, in 1734. On the feast of the Holy First Martyr Stephen, he ordained me a subdeacon, on the New Year, that is, on the day of memory of Basil the Great, turned me into monk Basil, without changing my name, as I asked, for the sake of helping me and the intercession of the Holy Hierarch of Christ” [Stranstvovaniya 1886:129].

References

1. Buzykina 2020 (in print) — Buzykina, Y.N. (2020). Vassiliy Grigorovich-Barskiy sketching architecture. Questions of the History of World Architecture (in print) (In Russ.)

2. Buzykina 2020 — Buzykina, Y.N. (2020). Vassiliy Barskiy as the first Russian researcher of the Christian East. Russian Journal of Church History. 1(1), 13-21. doi:10.15829/2686-973X-2020-1-3. (In Russ.)

3. Kondakov 1904 — Kondakov, N.P. (1904). Archaeological journey to Syria and Palaestina. St Petersburg, Academy of Sciences publ. p. 456. (In Russ.)

4. Lawrence 2015 — Lawrence, T.E. (2015). Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Transl. into Russian G. Karpinskiy. Moscow, Colibri publ. p. 672. ISBN 978-5-389-09705-6. (In Russ.)

5. Pozdnjakov 2018 — Pozdnjakov, V.A. (2018). Syria and the Syrians. History, Culture, Traditions and Customs, Monuments. Moscow: Putnik Pub. p. 816. (In Russ.)

6. Rineker 1891 — Rineker, F. and Mayer, G. (1891). Hauran. Nikifor, archim. Illustrated full popular Bible encyclopaedia. In 4 vols. Vol. 2. Moscow, A.I. Snegireva publ. Reprint: Moscow: Terra, 1990). p. 904. (In Russ.)

7. Stranstvovaniya 1885 — (1885). Wanderings of Vassiliy Grigorovich-Barskiy in the Holy Places of the East in 1723-1747. Issued by Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society, ed. by N. Barsukov, part 1. St Petersburg, Kirschbaum Publ. Reprint: Moscow: ichthys Publ. 2004. p. 533. (In Russ.)

8. Stranstvovaniya 1886 — (1886). Wanderings of Vassiliy Grigorovich-Barskiy in the Holy Places of the East in 1723-1747. Issued by Imperial Orthodox Palestine Society, ed. by N. Barsukov, part 2. St Petersburg, Kirschbaum Publ. Reprint: Moscow: ichthys Publ. 2005. p. 444. (In Russ.)

9. Architecture 1903 — (1903). Architecture, Sculpture, Mosaic and Wall-Painting in Northern Central Syria the Djebel Hauran. Part 2 of the Publications of an American Archaeological expedition to Syria in 1899-1900 under the patronage of V. Everit Macy, Clarence M. Hyde, B. Talbot B. Hyde and I.N. Phelps Stokes. Architecture and other arts by Howard Crosby Butler, A.M. New York. p. 466.

10. Burckhardt 1822 — Burckhardt, J.L. (1882). Syria and the Holy Land. Published by the association for promoting the discovery of the interior party of Africa. London: John Murray, Albemarle street. p. 668.

11. De Bruyn 1698 — De Bruyn, С. (1698). Reizen van Cornelis de Bruyn door de vermaardste deelen van Klein Asia, de eylanden Scio, Rhodus, Cyprus, Metelino, Stanchio, etc., mitsgaders de voornaamste steden van Aegypten, Syrien en Palestina. Delft, Henrik van Krooneveld. p. 398.

12. De Vogüé 1868 — De Vogüé, M. (1868). Syrie Centrale. Paris, Baudry.

13. Dentzer 1993 — Dentzer, J.-M. (1993). Siedlungen und ihre Kirchen in Südsyrien, in: Erwin M. Ruprechtsberger (Hg.), Syrien. Von den Aposteln zu den Kalifen (Linzer Archäologische Forschungen Band 21) (Ausstellungskatalog Stadtmuseum Nordico), Linz. pp. 82-101. ISBN: 3-8053-1609-7.

14. Fartacek 2003 — Fartacek, G. (2003). Pilgerstätten in der syrischen Peripherie. Eine ethnologische Studie zur kognitiven Konstruktion sakraler Plätze und deren Praxisrelevanz. 219 Druckseiten, 65 Farbabbildungen. Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, (Sitzungsberichte der phil.-hist. Klasse 700. Band; Veröffentlichungen zur Sozialanthropologie Nr. 5). p. 219. ISBN: 3-7001-3133-X.

15. Hage 2007 — Hage, W. (2007). Das orientalische Christentum. Die Religionen der Menschheit. Bd 29, 2. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer Verlag. p. 548. ISBN: 97831701766833170176684.

16. Hütteroth 1977 — Hütteroth, W.-D., Abdulfattah K. (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen. Germany: Erlangen: Die Frankische Geographische Gesellschaft. p. 225. ISBN: 3-920405-41-2.

17. Karnapp 1966 — Karnapp, W. (1966). Das Kuppelproblem von St. Georg in Ezra (Syrien). Walter Nikolaus Schumacher (Hrsg.). Tortulae. Studien zu altchristlichen und byzantinischen Monumenten. Festschrift für Johannes Kollwitz. Herder, Rom/Freiburg/ Wien. pp. 178-186.

18. Lassus 1932 — Lassus, J. (1932). Deux eglises cruciformes du Hauran. Bulletin d’etudes orientales, 1. p. 308.

19. Lassus 1985 — Lassus, J. (1985). Izr‘a. St. Georg. Beat Brenk (Hrsg.): Spätantike und frühes Christentum. (Propyläen Kunstgeschichte) Ullstein, Frankfurt/Main. p. 351. ISBN: 3549056966/3-549-05696-6.

20. Messerer 1952 — Messerer, H. E. (1952). (Dipl. Ing. Architekt) Die Zentralbauten des Hauran. Das Kuppelproblem. DamaskusMünchen. p. 599.

21. Murray 1841 — Murray, J., Robinson, E. and Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea. A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. Boston: Crocker & Brewster. p. 613.

22. Odenthal 1983 — Odenthal, J. (1983). Syrien. Hochkulturen zwischen Mittelmeer und Arabischer Wüste. 5000 Jahre Geschichte im Spannungsfeld von Orient und Okzident (DuMont Kunst-Reisefuhrer) (German Edition): DuMont, Köln. p. 363. ISBN-10: 3770113373; ISBN-13: 9783770113378. p. 363.

23. Piccirillo 2002 — Piccirillo, M. (2002). Arabie chrétienne: Archéologie et histoire. Editions Mengès, (In French). p. 259. ISBN: 2856204252.

24. Porter 1855 — Porter, J.L. (1855). Five years in Damascus: including an account of the history, topography, and antiquities of that city: with travels and researches in Palmyra, Lebanon, and the Hauran. London, John Murray, Albemarie Street. vol. 2. p. 452.

25. Restle 1971 — Restle, M. (Hrsg.) (1971). Hauran. Reallexikon zur byzantinischen Kunst. Durchzug durch das Rote Meer bis Himmelfahrt. Reihe: Reallexikon zur byzantinischen Kunst. Bd. 2. 1278 stolp. ISBN: 978-3-7772-7122-4.

26. Restle 1989 — Restle, M. (1989). Les Monuments chretiéns de la Syrie du Sud. Archéologie et histoire de la Syrie. Vol. 2 Saarbrücken. pp. 373-384. ISBN: 3-925036634-2. (In French)

27. Restle 1984 — Restle, M. (1984). Zur Baugeschichte der Georgkirche zu Azra. ΒΥΖΑΝΤΙΟΣ: Festschrift für H. Hunger zum 70 Geburtstag, ed. W. Hörander, J. Koder, O. Kresten & O. Trapp. Vienna. pp. 261-266.

28. Sartre 1985 — Sartre, M. (1985). Bostra: des origines à l‘Islam. Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, p. 279. ISBN: 2705302700. (In French)

29. Sartre 1991 — Sartre, M. (1991). L’Orient romain. Paris, Éditions du Seuil. P. 639. ISBN: 2020127059.

30. Scheck 1999 — Scheck, F.R. and Odenthal, J. (1999). Syrien (Taschenbuch) Hochkulturen zwischen Wittelmeer und Arabische Wüste. Köln, DuMont Kunst Reiseführer. Sp. 472. ISBN-10: 9783770139781, ISBN-13: 978-3770139781.

31. Sharon 2007 — Sharon, M. (2007). Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum Palaestinae, Addendum. Brill. xx, pp. 196, pp. 48. ISBN: 978-90-04-15780-4.

32. Waddington 1870 — Waddington, W.H. (1870). Inscriptions Grecques et Latines de la Syrie. Recueillies et Expliquées. Paris, Firmin Didot Frères, Fils et Cie. p. 744.

About the Author

Yulia N. BuzykinaRussian Federation

Yulia N. Buzykina, candidate of art history, researcher

yuliabuzykina@kremlin.museum.ru

Review

For citations:

Buzykina Yu.N. Vassiliy Barskiy discovering the Christian Architecture in Syria. Russian Journal of Church History. 2020;1(2):22-34. https://doi.org/10.15829/2686-973X-2020-2-21